“Niggas wanna shout, I’ma make noise…”

I was 11 years old when I first heard Earl Simmons in- retrospectively- possibly the most ill-fitting space possible. Ma$e, Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, and No Limit Records were the soundtrack of my childhood. And Tupac. Ostentation, melody, and the wonderfully nascent New Orleans bounce melody. And Tupac. It was what resonated and became the foundation of what I believed to be what rap music embodied. Tupac died and the ostentation and melody marched on triumphantly. It was so sumptuous and magnificent and excellent. It was goals and joyfulness and hope that I could dance in all white in a desert for no reason other than simply having the means to do something so absurd. Tupac meant a lot to me even then, but PUFFY AND MA$E WERE ON A HELICOPTER WITH MARIAH CAREY IN A SKINTIGHT SWIMSUIT IN GOD KNOWS WHERE. Young, malleable me imprinted that and correlated it with being successful. And happy. That was all rap needed to be at that point.

“Let my man and them stay pretty, but I’ma stay shitty/Cruddy, did it all for the money, is you with me?”

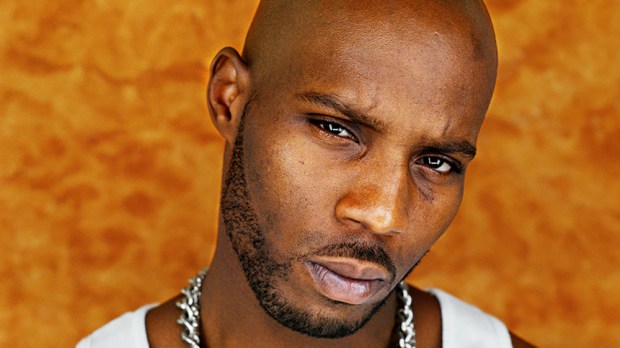

Mentioning Bad Boy Records is important to understand DMX’s impact as an artist certainly, but even more so as the beloved icon he became during his lifetime. His rise is inextricably linked to Bad Boy, but only in the context of what he was not. Puff worked with X and featured him twice on that Ma$e album, but only in the capacity to further Ma$e’s credibility with those that would never be carefree and rich and drunk on a body of water with Mariah Carey in a skintight swimsuit in God knows where, as was Bad Boy’s aesthetic at the time. When the opportunity came to sign DMX, Puffy knew he didn’t fit into that ethos and couldn’t be glossed up by the 1970s samples and opulent lifestyle that the late Notorious B.I.G. flawlessly (and inexplicably) pulled off. It wasn’t a mutual fit, and for all the questionable things Puffy/Diddy/P. Diddy/Papa/Papa Diddy Pop probably needs to answer for over the course of his career, this was not one of them.

“I wanna break bread with the cats I starve with/Wanna hit the malls with the same dogs I rob with”

X was quite literally a born loser. He said it himself. He talked about robbing people with the introspection of a person that hated the circumstance, but not necessarily the action itself. However, everything he did was in spite. In spite of the circumstance. In spite of chance. In spite of consequence. Rap is rooted in overcoming odds. But DMX overcame the Goddamned IMPOSSIBLE at a Goddamned impossible time. I could and would talk about his career objectively forever, and I really mean forever. But this is not about that. Not quite. This is why what he wasn’t meant so much to ME.

The spring of 1998 was a line of demarcation that defines me to this very day. The innocuous joy and blissful stupidity slipped out of my view from the window of a two-door Ford Explorer as my mother and I made our way from MY home in West Nashville to a place that somehow felt simultaneously relative and foreign in Washington, DC. Nothing was new to me, yet everything seemed novel. This wasn’t anything I was unfamiliar with, yet the status quo readjusted itself unbeknownst to my sensibilities. It was a shock, and I am ever so grateful for it.

It’s Dark and Hell is Hot brazenly pulled an entire group of rap fans that became comfortable with its’ luxurious bluster into the hungry, raw, and incredibly conflicted world that was Earl Simmons. It was an inflection point that essentially derided everything rap was, and became something that rap was allowed to be going forward. There was no bliss because in this world blissfulness and delusion were synonymous; here, reality trumped ecstasy. Everything seemed relatable, yet foreign in DMX’s world. You could have very well been the person X was, because that was the microcosm he drew you into. But most of us weren’t that at all, yet we stayed to not only root him on, but to love this man. DMX never scared me. If anything, I spent more time being scared that the lingering demons he spoke so often and candidly about would swallow him way too prematurely. I feared that maybe he wouldn’t get to see his impact during his lifetime. And in his death, it was very evident this was never the case.

Like so many of the prevailing themes in his music, I was conflicted about the possibility DMX would not make it through. When it became more evident that this fight was not one he would find a way to win, my thoughts went to his family and the people close to him that helped assuage our collective grief by their beautiful and illuminating insights, stories, and anecdotes about Dark Man X. They made me feel good about the life the man lived and the happiness that he was able to enjoy while he had the opportunity to do so. It made his passing a celebration. And what immediately hit me afterward were two things: the man’s life became an extension of our own simply from his existence; and I feel shitty for being so entitled to that access.

“Y’all been eatin’ long enough, dawg, stop being greedy”

There’s a platitude commonly used in sports that just kept reverberating in my mind after his passing: he left it all on the floor. That everything a person had to give was exhausted for the sake of competition, and the adoration of his or her fans and detractors alike. The notion that when an athlete walks away, we the fans are placated with the idea that it was all done FOR US. That somehow the object of our affection, scorn, and criticism could somehow sleep easier knowing that the people that shouldn’t matter thought he or she did a good job. And I hate applying this to DMX, but the parallels are unmistakably present in a way that many other artists are lucky to never be beholden to. DMX gave us his heart; he allowed us to celebrate with him, while being vulnerable enough to introduce and accept his weaknesses. It was the hope that he would always find a way to rise above, to be better than we could ever hope to be in light of our OWN circumstances, much less his own. It was the self-deprecation that he invoked in his misgivings. It was the light that shone off of his genuine amazement that he became what he became. It was so much. Too much for us, really. And it’s why I feel such joy for having this person in our collective lives. Because we never deserved him. And at the same time, I feel very comfortable expounding on his meaning to ME. DMX reveled in intimacy in so many ways that it became selfishly hard to let him go. HE BELONGS TO US GOD, PLEASE DON’T TAKE HIM FROM US became, in so many iterations, how every single one of us felt. It became the moment when we realized the champion and fighter needed to win one more incredibly overmatched battle, very much in the ways cancer, ALS, and the like, compel us to urge our loved ones to fight tirelessly for our own sake. It’s out of a love forged from the uncertainty of life without their contributions, somehow well-intentioned and centered around our own adherence to someone else’s strength being our own when it was never ours to begin with.

The scariest thing about letting him go is admitting that his incredible resilience bolstered my own. That his 50 years on this earth were not wrought by struggle so much as an otherworldly ability to overcome it. That this nigga was simply not human, and maybe he could be as fallible as humans tend to be. The beauty of DMX for me laid within the idea that the soul he bared to us was one so flawed that his unbelievable talent on a microphone both superseded and served to reinforce the notion maybe there is greatness in all of us, when that is a wholly fictional and nonexistent concept in large. What he was…IS…is a beacon. An ideal. The image of the good inside of us in spite of. None of us will ever be him, but IN HIM we felt less haunted by what our imperfections can obfuscate. He was strong because he was exceptional, and I am me because of the belief that I could be exceptional too. I thank you, DMX, for that. I thank you for showing me strength doesn’t reside solely in apathy or indifference. I thank you for showing me that being true to self is not weakness. I thank you for…just being. And I thank your family so much for understanding his willingness to give so much to us, entirely aware of how much people such as myself needed that validation to turn pain into light.

A.J. Armstrong is the creator of The Fly Hobo and His World of Oddities